I hate to sound like such a rube, but when Netflix called me last summer and asked me to do an interview about my reporting on a serial killer, Ted Bundy, I was barely aware of who or what Netflix was.

Since I watch very little television outside of occasional newscasts, I was blissfully ignorant of the existence of that movi- streaming behemoth. In fact, the last movie I actually watched was probably one of the early Star Wars movies, and I only went because my oldest son and daughter-in-law insisted on taking me.

My on-air ad-libbing skills were notoriously amateurish, although I had spent several years hosting telephone talk shows on radio stations KTW and KBLE. In those days working for a talk show paid minimum wage so there was very little money to be made. I turned that around by selling radio ads for my own shows and was given a 30% commission on each advertising contract I sold. Being an aggressive salesman actually made me one of the higher paid employees at those two stations, and I was able to start paying for my own college tuition.

But when the siren call of Top 40 radio reached me, my teenage ego took over and I gave up talk shows to enter the crazy world of ‘rock jockdom.’ Mind you, my awful on-air ad-libbing made me a poor candidate for a position as a rock jock. But KJR was losing its well-known news beat reporter, Tim Burgess. Over the next few weeks, Tim took me around the Seattle beat to meet his frequent news sources, including the Mayor, the various police departments, and most famous of all, Harley Hoppe, the overly talkative King County Assessor. In fact, Hoppe was so popular among city officials that when I couldn’t get details on behind-the-scenes stories and scandals I could always use his name to pry open doors and get details that were hidden from most other reporters.

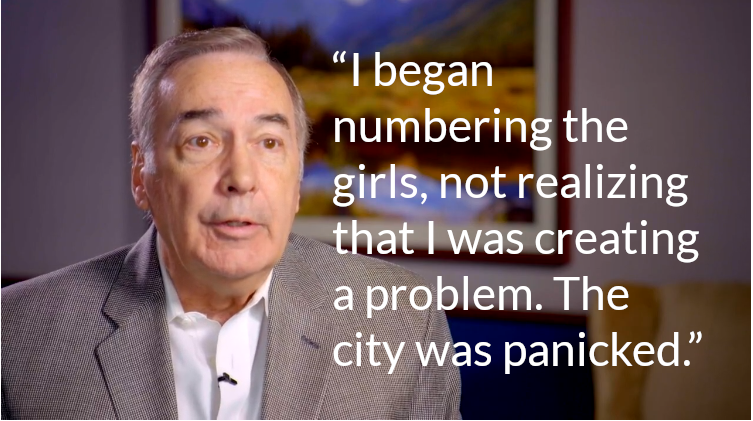

I was probably the first Seattle reporter on the scene of the early rapes and murders of young women in the Pacific Northwest. In the University district, on Queen Anne Hill, In Burien and Bellevue, women began going missing. The M.O. was almost always the same: an attractive young girl, long hair parted in the middle, would vanish from a site, sometimes in broad daylight, and weeks or months, or even years later the body would be found on some heavily wooded hillside around the King County area. Wooded areas in the Northwest are unlike woods around the rest of the country. Because of all the rain, the woods in Washington and Oregon are so choked with fast-growing vegetation, stinging nettles and thorn-covered blackberry bushes that they’re almost impossible to get through. Whoever was murdering all those girls was well-aware that a body dragged into those woods would quickly decompose in the moisture and animals would scatter the bones destroying most of the evidence so that very few clues would be left behind. By the time homicide cops discovered the murder scene, there wouldn’t be much left besides some clothing fragments and possibly a skull, from which a few teeth might be recovered.

The term, ‘cub reporter,’ annoys me a little, but that’s exactly what I was. But my reputation among police departments in the Pacific Northwest was pretty good. I was invited along on many police investigations and I got a good look at the gruesome world of homicide cops and their investigations. Since I carried no camera and only used an audio tape recorder, my presence wasn’t terribly intimidating to homicide and vice cops and I was invited into some of their more notorious cases.

One gruesome scene was on a hillside a hundred miles south of Seattle. Homicide cops walked me a mile up the hillside, far from any road or trail. As we climbed the hill I saw two investigators using a wood frame fastened to a square of wire mesh. They were shoveling dirt from the forest floor onto the mesh and gently shaking it to isolate bone fragments. As we approached the scene one of the plain-clothed cops suddenly let out an Indian ‘war whoop’ and began dancing around the spot, yelling, “I found a tooth! I found a tooth! The two officers who’d escorted me up the hill explained that finding a tooth was about the only way they could come anywhere close to identifying a victim.

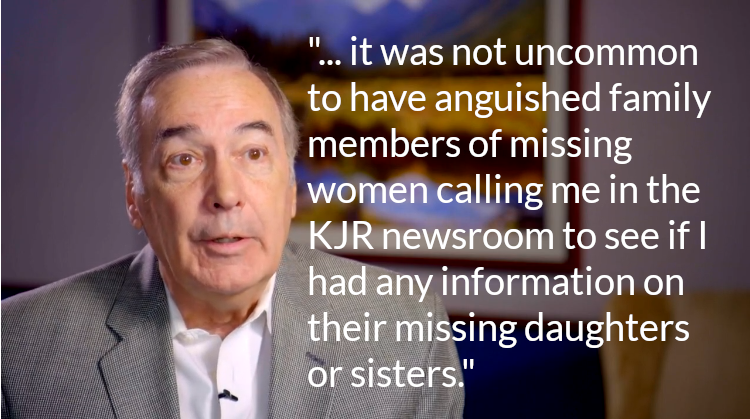

DNA evidence in the early 1970s was a pipe dream to most investigators. It didn’t become a forensic evidence tool until at least a decade later. I seriously doubt that murder was ever solved or even tied to Ted Bundy. In any event, it was not uncommon to have anguished family members of missing women calling me in the KJR newsroom to see if I had any information on their missing daughters or sisters. But much like a war correspondent, there’s so much grief and brutality and trying to support grieving families that at some point you just want to escape the nightmare.

My escape was July 18th of 1976 when I arrived in Denver to resume my career in a different state. It didn’t exactly work out that way. A few months after I took over the job with 9News, the nationally known Denver TV station, I noticed some missing girl homicides in the Aspen area. The M.O. was identical to the killer who’d been tormenting the Pacific Northwest. I tried to explain to my news director that this has to be connected to the Seattle killings and asked him to fly me to Aspen. “No dice,” he said. “It’s not a 9News story.” I tried to explain that it was definitely a national story but his repeated response was that since we don’t broadcast into Aspen it’s not a Denver TV news story. No argument convinced him.

Well, I had an emotional response which could and probably should have resulted in my immediate firing for insubordination. I vanished. Disappeared. Paid for tickets in a small private plane for my photographer and me to fly to Aspen. From there we began reporting on the Ted Bundy story in earnest. In fact, after Bundy escaped from the Pitkin County Courthouse, my photographer and I spent days driving up and down the streets and hillsides around Aspen hoping that we might see Bundy and give him a ride, hopefully back to the arms of the cops. That never happened. But suddenly, we were joined by news teams from all over the country. Yes, it became a national story. And I didn’t get fired. Insubordination is my middle name.

Back to the Netflix interview, I had no idea Bundy would suddenly become a national news sensation forty years after the fact. But between that broadcast and a headline in the Denver Post, the Bundy story has once again rippled across the country.

WATCH THE FULL 9NEWS INTERVIEW BY CLICKING ON THE IMAGE BELOW:

One of three books Ward has written since his retirement is about overcoming some of life’s annoying obstacles. It’s called Sometimes, Ya Gotta Ride The Elephant.

One of the chapters has never-before-published details of Ward’s coverage of Ted Bundy, including an incident in which Ward’s supervisor at a Seattle radio station demanded he do an unethical and illegal ‘stunt’ in his investigation of the Bundy story.

Ward refused and the ‘stunt’ was assigned to another reporter. Ward began looking for a new job leading to his career as an award-winning television investigative reporter and news anchor.

BUY NOW FOR $19.95 FROM WARD LUCAS via PayPal